There are plenty of hideouts in the rugged terrain of the Ozark Mountains, from abandoned cabins and campsites in vast forests where searchers are hunting for an ex-lawman known as the “Devil in the Ozarks.”

Others are not only off the grid but beneath it, in the hundreds of caves that lead to vast subterranean spaces. As local, state and federal law enforcement entered the third day of the search, they continued to scour the region around the prison.

“Until we have credible evidence that he is not in the area, we assume that he’s probably still in the area,” Rand Champion, a spokesman for the Arkansas Department of Corrections, said at a press conference on Wednesday.

Fugitive Grant Hardin “knows where the caves are,” said Darla Nix, a cafe owner in Pea Ridge, Arkansas, whose sons grew up around him. Nix, who describes Hardin as a survivor, remembers him as a “very, very smart” and mostly quiet person.

For the searchers, "caves have definitely been a source of concern and a point of emphasis," said Champion.

“That’s one of the challenges of this area — there are a lot of places to hide and take shelter, a lot of abandoned sheds, and there are a lot of caves in this area, so that’s been a priority for the search team,” Champion said. "It adds to the challenge of a search in this area, for sure.”

Impersonating an officer

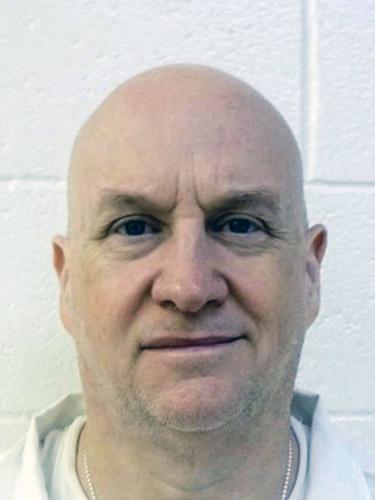

Hardin, the former police chief in the small town of Gateway near the Arkansas-Missouri border, was serving lengthy sentences for murder and rape. He was the subject of the TV documentary “Devil in the Ozarks.”

He escaped Sunday from the North Central Unit — a medium-security prison also known as the Calico Rock prison — by tailoring an outfit to mimic a law enforcement uniform, according to Champion. A prison officer opened a secure gate, allowing him to leave the facility. Champion said that someone should have checked Hardin's identity before he was allowed to leave the facility, describing the lack of verification as a “lapse” that is being investigated.

It took authorities approximately 30 minutes to notice Hardin had escaped.

Champion said that inmates are evaluated and given a classification when they first enter the prison system, and “based on what he’s assessed is the reason he was sent here.” There are portions of the Calico Rock facility that are maximum-security.

While incarcerated, Hardin did not have any major disciplinary issues, Champion said.

Authorities have been using canines, drones and helicopters to search for Hardin in the rugged northern Arkansas terrain, Champion said. The sheriffs of several counties across the Arkansas Ozarks had urged residents to lock their homes and vehicles and call 911 if they notice anything suspicious.

Dark places to hide

In some ways, the terrain is similar to the site of one of the most notorious manhunts in U.S. history.

Bomber Eric Rudolph, described by authorities as a skilled outdoorsman, evaded law officers for years in the Appalachian Mountains of western North Carolina. It was a five-year manhunt that finally ended in 2003 with his capture.

Rudolph knew of many cabins in the area owned by out-of-town people, and he also knew of caves in the area, former FBI executive Chris Swecker, who led the agency’s Charlotte, North Carolina, office at the time, said in the FBI's historical account of the case.

"I think it is very likely that he not only had campsites and caves, but he was also spending some time in those cabins," Swecker said.

“He was anticipating a great conflict and he had clearly lined up caves and campsites where he could go,” he added.

Rudolph pleaded guilty to federal charges associated with four bombings in Georgia and Alabama, including one in Centennial Olympic Park in downtown Atlanta during the 1996 Olympic Games.

There are about 2,000 documented caves in northern Arkansas, state officials say. Many of them have entrances only a few feet wide that are not obvious to passersby, said Michael Ray Taylor, who has written multiple books on caves, including “Hidden Nature: Wild Southern Caves.”

The key is finding the entrance, Taylor said.

“The entrance may look like a rabbit hole, but if you wriggle through it, suddenly you find enormous passageways,” he said.

Local residents might discover some caves as teenagers, so a fugitive would want to choose one that deputies in the search didn't also discover as teens, Taylor said.

It would be quite possible to hide out underground for an extended period, but “you have to go out for food, and you're more likely to be discovered,” he said.

Hardin pleaded guilty in 2017 to first-degree murder for the killing of James Appleton, 59. Appleton worked for the Gateway water department when he was shot in the head Feb. 23, 2017, near Garfield. Police found Appleton’s body inside a car. Hardin was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

He was also serving 50 years for the 1997 rape of an elementary school teacher in Rogers, north of Fayetteville.

He had been held in the Calico Rock prison since 2017.